|

| Stephen Dixon |

I always found it more difficult to get into Dixon’s story collections than his novels. At first, I am unable to read more than one story per day. Eventually, I really get into the books and try to read them in their entirety in a day because it feels like I have acquired the ability to enjoy more than one story in one sitting and if I don’t take advantage of this ability, I will lose it and go back to only being able to read one story per day. Since I don’t like reading story collections that way, I try to devour the entire book in one sitting if possible.

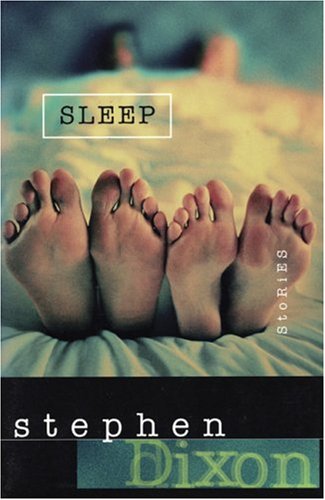

I checked his collection, Sleep, out from the library about 8 months ago. I was only able to get through a couple of stories before returning it because I had banned myself from reading adult fiction books to prepare for the endeavor of writing a novel for children. After finishing the novel, I checked the book out from the library again. I read a few stories here and there and it took me a while to gain the ability to enjoy more than one story per day. But I achieved the ability today and finished the book.

Regarding Dixon’s writing, he often uses protagonists who obsess over every decision and detail of their past, present, and futures. Obsessing about the future stands out in particular because the characters often consider the many ways in which events can occur in their lives and the stories include their rapidly changing speculations. I see this as a commentary on how every person on this planet is a storyteller because we all speculate about our futures, although perhaps not to the same extent as Dixon’s protagonists. This sort of speculation is very prominent in Sleep, or at least in the first fourth of the book or so.

I’m going to comment about a story that I read about a week or two ago: “The Stranded Man.” In the beginning, the protagonist starts out by describing his life on a deserted island and how he is lying in a hammock. Within a few sentences, he says, “Not quite a hammock. Nothing like one. On some dried grass, in a hut.” Upon reading this, it becomes a typical Dixon story. If this were a person’s introduction to his work, their sense of the story’s reality will be disrupted. For those who are already familiar with Dixon’s writing, these sentences reveal that the protagonist is imagining that he is on a deserted island. For about a page and a half, the protagonist continues to describe his life on the island and keeps changing his mind about certain details. Then it is revealed that he is not on a deserted island. Instead, he is at home, lying next to his wife in bed. He tells her that he was thinking about how he would be able to get himself to a deserted island that was thousands of miles from all bodies of land and be able to survive for years without being found. The idea of being alone is very appealing to him. The man’s wife does not seem bothered by this, but this is not a surprise in a Dixon story. The man tries to figure out how he would end up alone on a deserted island in a way that would not result in anyone’s death, but he cannot conceive of a scenario that would be successful. The wife suggests swimming to the island, but he says it would be too far. Neither he nor she come up with the idea that he could go alone to the island in a boat, although I suppose that wouldn’t work so well considering he would have a means to leave the island, but he could always destroy the boat. Soon, the man speaks of the “stranded man” of his fantasy as if he were a separate person from himself. His wife falls asleep and he continues to contemplate ways to reach the island. He imagines meeting a native girl and becoming her lover. They have children together. No, he never meets a native girl. He fantasizes that his wife is a native girl. After years, he is rescued. His island family comes back with him to the United States. No, they does not. His wife remarried while he was missing. He grows old and dies in the native girl’s arms. No, they go back to the island. Their children decide to stay behind and have children of their own. The man’s children sometimes visit their parents. He dies on the island. Or does he? — Bradley Sands, author of Rico Slade Will Fucking Kill You and editor of Bust Down the Door and Eat All the Chickens

No comments:

Post a Comment