I've been riding Grace's dick for a while now. Grace dick-riders give her props for an assload of different reasons—her feminist activism, her colloquial voice, her clever insight, etcetera—but what she's so brilliantly adept at, I think, is owning the shit out of her shit.

This probably sounds vague. Good. It's supposed to. What I'm essentially saying is that when I read a Grace story, I know immediately that it's a Grace story, and this is what implores me to refer to her by her forename and her forename only because I'm sure you know exactly who I'm talking about.

Take "Wants," for example, which was the first Grace story I ever read. "Wants" is chock-full of all the necessary requirements we so frequently want from our fiction: conflict, that conflict's progression, an enormous change at the last minute. The thing, though, is that none of these elements are existing on their own but instead are eloquently unified for the sake of survival. It's sort of like what Gary Lutz said about words that are destined to belong together: without all of Grace's eloquences working towards one poignant whole, there would be no ripple effect, no rocking of the boat, and no Grace dick-riders.

And this, I argue, is what all fiction (or short stories or poems or novels or bathtubs) should be striving towards: an immense sense of ownership over the craft, a unity so strong that every last syllable is riding the current of one subtle ebb tide, easily drifting towards its own narrative coast so its readers can find it buried in sand. I'm supposed to be this romantic when I'm talking about these things, you see. If not, our stories will be lost forever, drifting further and further along on the endless current of boring, predictable prose. — Mark Cugini, editor of Big Lucks

Friday, May 27, 2011

Sunday, May 22, 2011

Todd Orchulek on The Lime Twig by John Hawkes

Ever wonder what would happen if those things you dream about but never, ever tell anyone about came true? Ever wonder what it would be like to live out your most depraved fantasies, you know, the ones that only come creeping out of your subconscious under the cover of darkness, behind the shadow of dream? Well, John Hawkes certainly has, and he was kind enough to share. The Lime Twig is the thing, and it’s a fever I have never quite gotten over. I first read it the summer before transferring to UMass and it’s one of the things that Mike and I talked about at our first meeting, where I landed my internship, NOÖ style. It was fitting that I had read it in the haze of summer, in a field, under the watchful eye of shape shifting clouds. The free association feel felt right. I named clouds. I listened to the brittle music of Hawkes's narrative, snapping the lives of the bored Banks and the unfortunate Hencher in two. I watched them squirm under the long scrutiny of Hawkes's wish-fulfillment-gone-awry microscopic lens.

It all happens in the name of love, somehow, for as Hawkes says, “Love is a long scrutiny like that.” If you know nothing else about Hawkes’s style, you should know that. The quote is applicable to the whole. The narrative lens filters like consciousness itself. It’s discriminatory, distracted and spastic. But there’s always love and there’s always terror; the two are forever inextricably intertwined, just like in life. And that’s what it’s all about, really. It’s like a study in love and terror and desire and the places where those things meet, and it’s all wrapped up in a tasty poetic prose tortilla. There’s also a horse and kidneys cooling on the ledge. Hawkes's other works - The Blood Oranges, or Death, Sleep and the Traveler explore similar areas, but in different ways, mostly without the overt sense of terror, and without the sinking feeling that The Lime Twig can give you. The Cannibal might be a sister to The Lime Twig, and, really, you can’t go wrong reading any of his stuff if you’re even a tiny bit curious. Finding Hawkes was, for me, like stumbling across some fantastic secret or discovering some previously unknown, underground band that you feel right away, from the first beat, the first note. I remember, straight off, I wanted to simultaneously share and not share it, him, with the rest of the world. I wanted to keep him all to myself, but in the end I knew I couldn’t do that. He’s too good. So here I am, shouting from the rooftops.

It’s that long sense of scrutiny that holds it all together, all the out of focus elements, the fuzzy in-betweens, the moments of reflection. Hawkes' ability to hone in on the most minute details renders certain scenes lucid, even transcendent. You’ll feel like you’re dreaming, or reading a dream, if that’s even possible. Some say it isn’t, but I disagree. I’ve done homework in dreams before. Yes, that’s about as exciting as it sounds, and no, that wouldn’t be an example of the kind of dream Hawkes' is talking about here. So don’t worry, or do, if you’re afraid of the dark, because this book is full of shadows. Read it in a well lit room. The narrative thrust oftentimes leads you into moments of uncomfortable clarity precisely because of its capacity to convey a sense of terror with a single image. Or just clarity, depending. You’ll find yourself immersed in an image, a smell, a sound—the smell of lime, the image of the horse, a pair of buttocks, or the sound of footsteps a floor below. You’ll wonder how you ended up there, but not how the narrative ended up there. And that’s an important distinction, because wherever the story goes, it feels right, even when things go wrong. It feels hyper real. You don’t wonder about it, while you’re reading, because it’s so brilliantly rendered. It’s only after you’re done (which won’t be long – at 175 pages, it is more novella than novel) that you stop and think, wait, what?

And the imagery haunts. Measured against those moments of intense, long scrutiny, the rest of the time things simply aren’t as clear, as is often the case with life, or dreams. That’s where it becomes, for me, “magic time” as Kevin Spacey would say (doing his best Jack Lemon impersonation), because it is a dream, after all. And like a dream, this novel is filled with those moments of transition, where identity and focus become blurred and fuzzy—people go in and out of focus, images appear and disappear, time speeds up or slows down without you even noticing. And then, boom goes the dynamite, things suddenly snap back into focus. And it’s a clear, lucid, sick focus that Hawkes throws at us. It’s a sharp, frayed, lyrical focus.

As for the story, well, Hencher’s the way in. He’s a fat man, missing his mother, living in the past. He finds a new outlet for his loyalty, the misoneist Banks, Michael and Margaret. Hencher wants to please them, to show what a loyal dog he really is, so he decides to help Michael fulfill his dream, owning a race horse. It’s a dream that everyone seems privy to, Michael and Margaret and Hencher, too. It affects all of them, the dream and the horse. Their lives and relationships are inextricably tied to that horse, Michael’s dreams, and their own.

“You may manipulate the screen now, William,” Hencher’s mother tells him in flashback, and he does. Hawkes does, too, subtly shifting perception and summoning tension at will, with a deft turn of phrase, or an image, suspended. He messes with holotropics, hanging the image of the horse in the middle of the narrative, in the Banks’ apartment, teasing and toying with the reader and reality. It’s unnerving, but an effective narrative mechanism:

“Knowing how much she feared his dreams; knowing that her own worst dream was one day to find him gone, overdue minute by minute some late afternoon until the inexplicable absence of him became a certainty; knowing that his own worst dream, and best, was of a horse which was itself the flesh of all violent dreams; knowing this dream, that the horse was in their sitting room-he had left the flat door open as if he meant to return in a moment or meant never to return-seeing the room empty except for moonlight bright as day and, in the middle of the floor, the tall upright shape of the horse draped from head to tail in an enormous sheet that falls over the eyes and hangs down stiffly from the silver jaw; knowing the horse on sight and listening while it raises one shadowed hoof on the end of a silver thread of foreleg and drives down the hoof to splinter in a single crash one plank of that empty Dreary Station floor; knowing his own impurity and Hencher’s guile; and knowing that Margaret’s hand has nothing in the palm but a short life span (finding one of her hairpins in his pocket that Wednesday dawn when he walked out into the sunlight with nothing cupped in the lip of his knowledge except thoughts of the night and pleasure he was about to find)-knowing all this, he heard in Hencher’s first question the sound of a dirty wind, a secret thought, the sudden crashing in of the plank and the crashing shut of that door.”Once Michael gets involved with Hencher and his mob friends, things begin to change for everyone, and not for the better. Michael is spared, for a spell, and gets to live out his most lurid fantasies. Margaret and Hencher, well, not so much. It all quickly devolves into a nightmare from there. The chrysalis doesn’t change into a butterfly, but a beast.

What Hawkes does best is manipulate time. In this study of reality vs. unreality, or fantasy vs. nightmare, this has the greatest effect on the narrative. He has it on a string throughout, speeding it up, slowing it down, or suspending it altogether. He flashes forward, flashes back. He does away with it completely when it becomes burdensome. This allows the terror to bloom fully within the reader’s mind. And the image of the horse resonates and echoes throughout, from start to finish, for temporality has no dominion in the realm of dream or nightmare. For

Michael, and for me, it carries with it an eerie, undeniable sense of jamais vu.

Michael, and for me, it carries with it an eerie, undeniable sense of jamais vu.So, be careful what you wish for, or, at least, remember what that old adage, “if you can’t be good, be careful,” because who knows, there might be a horse out there somewhere with your name on it.

Thursday, May 19, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #11: Carolyn Zaikowski on The Little Prince

|

| Carolyn Zaikowski's tattoo: "I believe that for his escape he took advantage of the migration of a flock of wild birds." |

I do not say these things lightly nor to invoke cliché. The Little Prince is not just a "cute" book to me, my love of it not just a quirky or fun part of my identity. Each year I wonder, is this the right year to give it to my nephew, himself a little prince? At what age will he finally understand, and what does understanding mean? Perhaps it's I, in my self-satisfied adulthood, who has fallen from wonder and needs to be reminded that a plain hat and an elephant being eaten by a snake are not the same thing? I keep it next to my bed in a small pile of crucial books that includes Gandhi's autobiography, S.N. Goenka's guide to Vipassana Meditation, the Bhagavad Gita, and an archive of Thich Nhat Hanh. When a friend of mine died, it was The Little Prince we read at her funeral: "And at night you will look up at the stars. Where I live everything is so small that I cannot show you where my star is to be found. It is better like that. My star will just be one of the stars, for you. And so you will love to watch all the stars in the heavens... they will all be your friends. In one of the stars I shall be living. In one of them I shall be laughing. And so it will be as if all the stars were laughing, when you look at the sky at night. And when your sorrow is comforted (time soothes all sorrows) you will be content that you have known me." In my dark moments, I think of this. I go out to the hill behind my house, alone, and I am reminded of the expanse—sad here, glorious there, but every inch of which proves the impossibility of aloneness. When Antoine de St. Exupery's plane, which crashed and killed him in 1944, was found in 2004, a rush of heat filled my esophagus and pulse and I felt humbled with wonder. It is so good to remember wonder. "Is the warfare between the sheep and flowers not important? Is this not of more consequence than a fat red-faced gentleman's sums?" There is a small group of indigenous people in Argentina who speak Toba, a language into which only two books have been translated in modern memory: The Bible and The Little Prince. There is a reason why. — Carolyn Zaikowski, editor of Dinosaur Bees

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

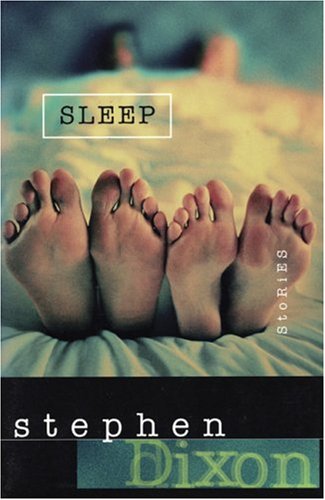

NOÖ Knows Stories #10: Bradley Sands on Stephen Dixon's "The Stranded Man"

|

| Stephen Dixon |

I always found it more difficult to get into Dixon’s story collections than his novels. At first, I am unable to read more than one story per day. Eventually, I really get into the books and try to read them in their entirety in a day because it feels like I have acquired the ability to enjoy more than one story in one sitting and if I don’t take advantage of this ability, I will lose it and go back to only being able to read one story per day. Since I don’t like reading story collections that way, I try to devour the entire book in one sitting if possible.

I checked his collection, Sleep, out from the library about 8 months ago. I was only able to get through a couple of stories before returning it because I had banned myself from reading adult fiction books to prepare for the endeavor of writing a novel for children. After finishing the novel, I checked the book out from the library again. I read a few stories here and there and it took me a while to gain the ability to enjoy more than one story per day. But I achieved the ability today and finished the book.

Regarding Dixon’s writing, he often uses protagonists who obsess over every decision and detail of their past, present, and futures. Obsessing about the future stands out in particular because the characters often consider the many ways in which events can occur in their lives and the stories include their rapidly changing speculations. I see this as a commentary on how every person on this planet is a storyteller because we all speculate about our futures, although perhaps not to the same extent as Dixon’s protagonists. This sort of speculation is very prominent in Sleep, or at least in the first fourth of the book or so.

I’m going to comment about a story that I read about a week or two ago: “The Stranded Man.” In the beginning, the protagonist starts out by describing his life on a deserted island and how he is lying in a hammock. Within a few sentences, he says, “Not quite a hammock. Nothing like one. On some dried grass, in a hut.” Upon reading this, it becomes a typical Dixon story. If this were a person’s introduction to his work, their sense of the story’s reality will be disrupted. For those who are already familiar with Dixon’s writing, these sentences reveal that the protagonist is imagining that he is on a deserted island. For about a page and a half, the protagonist continues to describe his life on the island and keeps changing his mind about certain details. Then it is revealed that he is not on a deserted island. Instead, he is at home, lying next to his wife in bed. He tells her that he was thinking about how he would be able to get himself to a deserted island that was thousands of miles from all bodies of land and be able to survive for years without being found. The idea of being alone is very appealing to him. The man’s wife does not seem bothered by this, but this is not a surprise in a Dixon story. The man tries to figure out how he would end up alone on a deserted island in a way that would not result in anyone’s death, but he cannot conceive of a scenario that would be successful. The wife suggests swimming to the island, but he says it would be too far. Neither he nor she come up with the idea that he could go alone to the island in a boat, although I suppose that wouldn’t work so well considering he would have a means to leave the island, but he could always destroy the boat. Soon, the man speaks of the “stranded man” of his fantasy as if he were a separate person from himself. His wife falls asleep and he continues to contemplate ways to reach the island. He imagines meeting a native girl and becoming her lover. They have children together. No, he never meets a native girl. He fantasizes that his wife is a native girl. After years, he is rescued. His island family comes back with him to the United States. No, they does not. His wife remarried while he was missing. He grows old and dies in the native girl’s arms. No, they go back to the island. Their children decide to stay behind and have children of their own. The man’s children sometimes visit their parents. He dies on the island. Or does he? — Bradley Sands, author of Rico Slade Will Fucking Kill You and editor of Bust Down the Door and Eat All the Chickens

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #9: Frank Hinton on sex stories

"I was alone in the house, my family was outside working in the garden and I snuck into my parent’s room and found a yellowed paperback called You Always Remember Your First Time. I didn’t understand what it was about but read the first story and discovered what sex was and maybe more importantly, what words could convey.

Up until then, sex had been a penis resting still in a vagina. I didn’t understand there was a motion to it. I knew nothing. The stories in the book expressed a kind of sadness about sex. They were filled with regret and pain. Some were happy and ecstatic. One story was about a very old man seducing a very young girl. I remember a description of tears sliding down chests and over nipples. I’ve thought of this happening to me when crying, in a vague, disconnected way.

I was fascinated. I re-stashed the book and found myself sneaking back to it every possible moment. I started to write stories about sex or really, about bodies moving together in uncomfortable/comfortable ways. I hid the stories in single folds between sheets of old coloring books and never re-read them. That summer I think I wrote maybe thirty ‘sex’ stories and became convinced that this was the ultimate form of fiction/expression. I think now, reflecting on this, that book has been an influence on me being a writer.

One day I went into the drawer with the book and it was gone. I’d always been careful to replace it exactly, but I was caught. Maybe. Maybe my parents had just tossed it out during a cleaning. I’d read every story 3-4 times and felt a solid ‘adult’ grasp of the metaphors and language used. My sex stories are still somewhere in a box, in a basement, in between poorly colored sheets. I haven’t thought about any of this in a clear and organized way for a long long time." — Frank Hinton, author of I Don't Respect Female Expression and editor of Metazen

Up until then, sex had been a penis resting still in a vagina. I didn’t understand there was a motion to it. I knew nothing. The stories in the book expressed a kind of sadness about sex. They were filled with regret and pain. Some were happy and ecstatic. One story was about a very old man seducing a very young girl. I remember a description of tears sliding down chests and over nipples. I’ve thought of this happening to me when crying, in a vague, disconnected way.

I was fascinated. I re-stashed the book and found myself sneaking back to it every possible moment. I started to write stories about sex or really, about bodies moving together in uncomfortable/comfortable ways. I hid the stories in single folds between sheets of old coloring books and never re-read them. That summer I think I wrote maybe thirty ‘sex’ stories and became convinced that this was the ultimate form of fiction/expression. I think now, reflecting on this, that book has been an influence on me being a writer.

One day I went into the drawer with the book and it was gone. I’d always been careful to replace it exactly, but I was caught. Maybe. Maybe my parents had just tossed it out during a cleaning. I’d read every story 3-4 times and felt a solid ‘adult’ grasp of the metaphors and language used. My sex stories are still somewhere in a box, in a basement, in between poorly colored sheets. I haven’t thought about any of this in a clear and organized way for a long long time." — Frank Hinton, author of I Don't Respect Female Expression and editor of Metazen

Friday, May 13, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #8: Tao Lin on Charles R. Johnson

"Two stories I like that I haven't discussed before on the internet (except here, where I also list other stories I like) are Charles R. Johnson's "China" (from his 1986 collection The Sorcerer's Apprentice: Tales and Conjurations) and "Kwoon" (from his 2005 collection Dr. King's Refrigerator: And Other Bedtime Stories).

"China," based on my memory, is about a man and his wife. In the beginning the wife is worried about her husband's failing health. She thinks things about what she'll do when he dies. Then the husband becomes involved in martial arts and becomes increasingly healthier and more "Zen," to a degree that the wife, somewhat confused about why she feels this way, becomes disapproving of the husband's behavior and, in her view, seeming self-righteousness. The story ends with the wife watching the husband doing a jump-kick and crying upon realizing that she is going to die before her husband dies.

"China," based on my memory, is about a man and his wife. In the beginning the wife is worried about her husband's failing health. She thinks things about what she'll do when he dies. Then the husband becomes involved in martial arts and becomes increasingly healthier and more "Zen," to a degree that the wife, somewhat confused about why she feels this way, becomes disapproving of the husband's behavior and, in her view, seeming self-righteousness. The story ends with the wife watching the husband doing a jump-kick and crying upon realizing that she is going to die before her husband dies.

"Kwoon," based on my memory, is about a person who is teaching martial arts. He is alone, seems to have no friends or family, and lives in the same location where he teaches. He seems older, maybe in his 30s or 40s, and to have a resigned view of life. One day a new student challenges the person and beats him badly in front of his students, embarrassing him. Most of the students begin training with the new student. The story ends with the person and the new student both implying, or accepting, that they have things to learn from the other, I think.

"Kwoon," based on my memory, is about a person who is teaching martial arts. He is alone, seems to have no friends or family, and lives in the same location where he teaches. He seems older, maybe in his 30s or 40s, and to have a resigned view of life. One day a new student challenges the person and beats him badly in front of his students, embarrassing him. Most of the students begin training with the new student. The story ends with the person and the new student both implying, or accepting, that they have things to learn from the other, I think.Based on my memory both stories are in 3rd-person. I was reminded of Lorrie Moore when I first read "China." Both stories are ~20 pages. I think I first discovered Charles R. Johnson when I was trying to find writers who had an interest in Buddhism." — Tao Lin, author of Richard Yates

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #7: Kevin Sampsell on "What I Did" by Rebecca Brown

"Rebecca Brown is a fantastic writer of risky, dark fiction as well as some nakedly heartfelt nonfiction and works in other mediums. She lives in Seattle, Washington but her work is underappreciated in America (though apparently she is big in Japan), with the exception of gay readers and authors, who see her as a lasting influence.

In 1992, City Lights released her story collection, The Terrible Girls. This was right when I moved to Portland, Oregon. I bought this collection without knowing anything about the author. I simply loved the title and that cool cover design. I was still fairly new to book-reading and my early, impressionable interests were stories and novels that challenged censorship and had been banned—works by William Burroughs, Terry Southern, Karen Finley, Henry Miller, and folks like that.

Rebecca Brown fit perfectly into this misfit canon. One story in particular, 'What I Did,' shows up 2nd to last in this book and it's the one that felt transformative to me. It's a detailed story about a woman carrying some sort of duffel bag through a dark, desolate land. It's so dark that the woman can't even see the bag. She can't tell what it's made of and she feels no seams or weaves in its construction. She does not say what's in the bag (you learn that in the next story, 'The Ruined City'). She is only trying to get a place where she can bury it. It's a 10-page sensory sensation. There is nothing in the story except the woman and the bag and the action between them and the reader feels everything, in the dark, with her fingers and her sore, thirsty body.

I remember being so impressed with the story that I tried to write something similar (I vaguely recall something dangerously plagiaristic, like about a man carrying a box through a tunnel or something like that), but my story failed. I had nowhere near the talent of Rebecca Brown.

|

| Rebecca Brown, author of "What I Did" |

While I waited for a chance to say hello to RB, I met Stacey Levine, whose book, My Horse and Other Stories, remains one of my all-time favorite collections. Finally, I worked up the nerve to talk to Rebecca, and wouldn't you know it: she was super nice. Not like a "Terrible Girl" at all. Meeting her was one of my first lessons in the fact that authors, even if they write creepy, mentally tormenting tales, can be completely warm and normal and approachable. Rebecca and I became fast friends. She's been totally encouraging to me and my writing (and publishing) ever since.

Her own work has continued to be awesome (though I feel that it's still not as talked-about as it should be), from Dogs: A Bestiary to her recent essay collection, American Romances. For short story fans who haven't read her work, I say start out with The Terrible Girls or her 2006 collection, The Last Time I Saw You." — Kevin Sampsell, author of A Common Pornography and publisher of Future Tense Books

Tuesday, May 10, 2011

"It is totally appropriate to have alien sex in public, even on their planet." — Alicia LaRosa on Lizzy Acker's Monster Party

Monster Party, by Lizzy Acker, is a genius collection of short stories that tie together the reality of interpersonal relationships, human and not.

Each story, in and of itself, is beautifully crafted. Moving from different ages, children to adults, Acker pushes the boundaries of what is proper and what actually exists in reality. And then, just when you get comfortable with what you’re reading, feeling as if you could snuggle up with these people and their problems—the aliens visit. They don’t just visit, however. They show you how you simply love wrong, have sex the wrong way, and that you wouldn’t even know that they’re having sex right in front of you. But “it is totally appropriate to have alien sex in public, even on their planet.”

When you think you’re comfortable with those perfect, sexual aliens, different creatures show up that are even more bizarre in a wonderful, spectacular way. “I love you baby. Good luck with planet Earth.”

Personally, my favorite thing about this collection of stories is how one element, no matter how small—like an image or a feeling—finds its way into another story, another set. At first I thought I was imagining things—which isn’t a hard thing to do—but when the aliens and their lovemaking found their way into another story, in another set, I knew it was more deliberate than not. The bottle rockets, the basement: everything has its purpose. Nothing is left out. The hints and pieces of the puzzle are intricately laced into the full collection.

|

| Lizzy Acker, author of Monster Party |

These stories are full of such raw emotion, so much that it is impossible to put the book down until finished. The title story, “Monster Party,” is one of the most emotional stories of all, as repressed as it is. “I suddenly don’t want to tell him, but here I am. I have to. I put all the parts of the machine together all by myself and all that’s left now is to turn on the electricity.” As the reader, I wanted the narrator to scream, cry, punch, and kick her way into the heart of the man she cared about. “I try to think tougher, like a boy would, or like a terrorist or a serial killer. I open the party mix and my skateboard rolls around over my head.”

Soon, I will also take her initiative and put my name in multiple stories of my own collection. “This hasn’t occurred to me before and it seems like a brilliant solution, a dream solution.” Ballsy move, but one that emphasizes the emphasizable.

Soon, I will also take her initiative and put my name in multiple stories of my own collection. “This hasn’t occurred to me before and it seems like a brilliant solution, a dream solution.” Ballsy move, but one that emphasizes the emphasizable.

Each story is worth reading, down to the last word. Whether you can relate to the stories, pick them up and chew on them to reveal their taste, or simply stare at the words until they come together and slap you in the face with meaning—this book is worth the time.

NOÖ Knows Stories #6: Mark Baumer on the future of storytelling

"I once read a short story called, "I don't believe in the short story anymore." I forget who wrote it. I think I remember there being a man in a canoe. The man in the canoe was tired of his canoe. He burned his canoe and decided to just float in the water for a while. After an hour of floating in the water he began to wonder if he could swim. He became worried. He could see the remains of his canoe in the distance. He began to float towards these remains, but as he got closer he realized it was a barge of burning tires. The barge reeked. The man decided to stop moving towards the barge. He was not sure what to do. A few years passed. The man ate gullweed and salmon. The outer layer of his skin turned into a natural gortex. The man could float as easily as he could breathe. He still was not sure what he wanted to do with his life. One day a magazine floated by. He picked it up. The magazine was full of jetskis. The man became very excited. He ordered a jetski. He felt very happy when it arrived. He never thought about his old canoe or the burning barge of tires again." — Mark Baumer, who once walked across America and at another time ate pizza every day.

NOÖ Belly Flops Into the Wigleaf Top Short Fictions of 2010

Congratulations to everybody on the list of Wigleaf Top 50 Very Short Online Fictions of 2010! Including our Associate Editor Ryan Call and his sister Christy Call, NOÖ [12] illustrator, for their story "Snowstorm as Nostalgic Accumulation."

NOÖ had a strong showing in the long list, with 6 stories placing. Here they are in alphabetical order by author last name:

"Running the Drain" by Brian Allen Carr in NOÖ [12]

"Nine Reasons Not to Kill Yourself East of St. Marks" by Kyle Hemmings in NOÖ Weekly (Sep 20th edition guest edited by Thomas O'Connell)

"Everyone the Same, But Not at Once" by Cami Park in NOÖ [11]

"The News" by Julianna Spallholz in NOÖ Weekly (Sep 20th edition guest edited by Thomas O'Connell, double dunk, nice work Thomas!)

"A Staging" by Michael Trocchia in NOÖ [12]

"Case History #3: Catie" by Carolyn Zaikowski in NOÖ [11]

Congratulations to everybody, and thanks to Lily Hoang, Ravi Mangla, and Scott Garson of Wigleaf! Thanks to all the contributors, guest editors, and readers of NOÖ Weekly, and stay tuned for NOÖ [13], coming this summer!

NOÖ had a strong showing in the long list, with 6 stories placing. Here they are in alphabetical order by author last name:

"Running the Drain" by Brian Allen Carr in NOÖ [12]

"Nine Reasons Not to Kill Yourself East of St. Marks" by Kyle Hemmings in NOÖ Weekly (Sep 20th edition guest edited by Thomas O'Connell)

"Everyone the Same, But Not at Once" by Cami Park in NOÖ [11]

"The News" by Julianna Spallholz in NOÖ Weekly (Sep 20th edition guest edited by Thomas O'Connell, double dunk, nice work Thomas!)

"A Staging" by Michael Trocchia in NOÖ [12]

"Case History #3: Catie" by Carolyn Zaikowski in NOÖ [11]

Congratulations to everybody, and thanks to Lily Hoang, Ravi Mangla, and Scott Garson of Wigleaf! Thanks to all the contributors, guest editors, and readers of NOÖ Weekly, and stay tuned for NOÖ [13], coming this summer!

Monday, May 9, 2011

"Perhaps the most frightening aspect of Call's stories is that he makes them seem so believable."

Check out the Emerging Writers Network's review of The Weather Stations, NOÖ Associate Editor Ryan Call's new book of short stories. Congratulations, Ryan!

"Each and every story has a human component that Call has written with such care, with such straightforward language, that we cannot help but get pulled in and root for them while they battle elements so much greater than they have the capacity to truly battle. They are doomed to lose and we know it, and they know it, and we know that they know it, but still we care and we root and that says a lot for the abilities of Ryan Call."

"Each and every story has a human component that Call has written with such care, with such straightforward language, that we cannot help but get pulled in and root for them while they battle elements so much greater than they have the capacity to truly battle. They are doomed to lose and we know it, and they know it, and we know that they know it, but still we care and we root and that says a lot for the abilities of Ryan Call."

Thursday, May 5, 2011

An Exclusive Interview with Ofelia Hunt

OFELIA HUNT might not be 100% real, but she writes 100% real books. Her first novel, Today & Tomorrow, is forthcoming from Magic Helicopter Press in a mere 10 days. To get the mills milling, our brave intern Alicia LaRosa ventured into a correspondence with the mysterious Hunt "herself." As we get closer to the release date, we might give you more details about who Hunt "really" is, or we might just link to pictures of Will Smith and tell you that's a clue to Ofelia's "real" name. Or we might just tell you to look on the copyright page of the book itself. The important thing to remember is that OFELIA HUNT IS BACK and MAY 15TH: THE TODAY TOMORROW COMES.

AL: In Today & Tomorrow, did you deliberately place "Tomorrow" smack in the middle of the book? (When it opens, "Tomorrow" is directly in the middle of the spine). Was it a precise, diabolical plan or was it an unconscious decision?

OH: I have many diabolical plans, but sadly, this was not one. I began with the restriction of two parts in two days and arbitrarily named them 'Today' and 'Tomorrow' in my Word document. Initially each 'day' was to have twenty-four chapters—which may have lead to the center placement of 'Tomorrow'. I abandoned the twenty-four chapter structure because it looked annoying in Word, and because Ofelia Hunt did/does not like paragraph breaks (and so every place where there was a paragraph break became a chapter).

OH: I have many diabolical plans, but sadly, this was not one. I began with the restriction of two parts in two days and arbitrarily named them 'Today' and 'Tomorrow' in my Word document. Initially each 'day' was to have twenty-four chapters—which may have lead to the center placement of 'Tomorrow'. I abandoned the twenty-four chapter structure because it looked annoying in Word, and because Ofelia Hunt did/does not like paragraph breaks (and so every place where there was a paragraph break became a chapter).

AL: Do you take on a specific persona as Ofelia Hunt? Do you dig deep within yourself to find this person, detach yourself from reality this way by projecting this personality, or do you simply act au naturale?

AL: Are any of the characters in the novel based off of people you know personally? Related to?

AL: If you had to pick one day of your life to live over and over again, just like Bill Murray did in Groundhog Day, which day would it be?

AL: Who is the man in the corner?

AL: In Today & Tomorrow, did you deliberately place "Tomorrow" smack in the middle of the book? (When it opens, "Tomorrow" is directly in the middle of the spine). Was it a precise, diabolical plan or was it an unconscious decision?

OH: I have many diabolical plans, but sadly, this was not one. I began with the restriction of two parts in two days and arbitrarily named them 'Today' and 'Tomorrow' in my Word document. Initially each 'day' was to have twenty-four chapters—which may have lead to the center placement of 'Tomorrow'. I abandoned the twenty-four chapter structure because it looked annoying in Word, and because Ofelia Hunt did/does not like paragraph breaks (and so every place where there was a paragraph break became a chapter).

OH: I have many diabolical plans, but sadly, this was not one. I began with the restriction of two parts in two days and arbitrarily named them 'Today' and 'Tomorrow' in my Word document. Initially each 'day' was to have twenty-four chapters—which may have lead to the center placement of 'Tomorrow'. I abandoned the twenty-four chapter structure because it looked annoying in Word, and because Ofelia Hunt did/does not like paragraph breaks (and so every place where there was a paragraph break became a chapter). AL: Do you take on a specific persona as Ofelia Hunt? Do you dig deep within yourself to find this person, detach yourself from reality this way by projecting this personality, or do you simply act au naturale?

OH: I'd like to say I put on a special bathrobe and eye makeup and kitten slippers. But I'm far more boring. I decided Ofelia liked a number of specific things and typed them out: 11 point Garamond, hyphens, repetition, trickery, 'math rock', parking lots… I made a list of writers Ofelia admires: Jean Rhys, Gertrude Stein, William Faulkner, Stacey Levine, Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, Kenneth Koch, Kurt Vonnegut, Lisa Jarnot, Diane Williams, Joy Williams, etc... Ofelia Hunt does not like or understand plot. Her favorite move is Suicide Club (a Japanese movie sometimes called Suicide Circle). I woke every day for about two years at four a.m. to write and revise for sixty to ninety minutes before work. This may have detached me from reality. I remember feeling tired a lot, and listening to a lot of hiphop. Ofelia often writes about the kinds of things I muse about throughout a day, the things I find funny or strange. I think of Ofelia as both the "I" in the novel and the writer of the novel, so the novel may be a memoir.

AL: Are any of the characters in the novel based off of people you know personally? Related to?

OH: No, or not really. At most, certain moments, memories, instances, are based on reality. I grew up near Highland Ice Arena, and throughout middle school the Friday night skate was the place to be. I'd like to say that every character is a composite of every person I've ever met if that composite had been born me. The grandfather character is probably the parent I wish I had, and to some degree, has a sense of humor very much like my mother's.

AL: If you had to pick one day of your life to live over and over again, just like Bill Murray did in Groundhog Day, which day would it be?

OH: Probably the day I moved to Portland with my partner. That day was full of possibility and exhaustion and carrot cake.

AL: Who is the man in the corner?

OH: I don't actually know. When I was very small, and sometimes even now, in darkness, as I pass near parked cars, the image of a very long arm reaching to grab my ankles appears in my mind. It is possible that this arm is the man in the corner.

Read excerpts of Today & Tomorrow in NOÖ Journal and Alice Blue Review. Stay tuned for more info about the novel and exclusive Ofelia Hunt secrets!

Read excerpts of Today & Tomorrow in NOÖ Journal and Alice Blue Review. Stay tuned for more info about the novel and exclusive Ofelia Hunt secrets!

Labels:

Ofelia Hunt

NOÖ Knows Stories #5: Guest Post by Bryan Coffelt

"A short story is a four or five minute stretch at a bus stop. Or a sac bunt vs. a "battle at the plate."

The short story is unfortunate, at least. Like when you fall weird on your wrist or ankle when making a gamble for something unimportant—or at least something inconsistent. Something hard to judge with your eyes. With your eyes. A short story does not start and stop, it just can be seen a little different. Maybe it's two different points in a river. At one point, you're having an MVP season with the San Francisco Giants, and then, holy shit! You're finishing your career with the Dodgers. I guess I'm saying my answer to the question is "Jeff Kent."" — Bryan Coffelt, poet and designer extraordinaire at Future Tense Books

I just told my cat, "No." He pawed a thumb drive off of a shelf. I think a short story would make a bigger thud if it fell off a shelf than a thumb drive, but less of a thud than a hand job that you somehow remember for a long time. Or maybe they are all the same thing: the thumb drive, the short story, and the hand job. Maybe even my cat is the same thing as a hand job.

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

"I cope with my life with a daydream in uniform."

Heart scratching gags, comments that offend Gretchen, nightcrawler worms, all manner of human documentary, floaters, and 101 ways to love a man without $exxx: just a few things from a 90s kids Haters Going to Hate NOÖ Weekly edition guest-edited by Richard Chiem. Featuring Luna Miguel, Steve Roggenbuck, Frank Hinton, Timothy Willis Sanders, and Ana C. Give it a gawk.

NOÖ Knows Stories #4: Guest Post by Jonah Vorspan-Stein

"Amy Hempel’s Reasons to Live is the only book I have ever read twice in one sitting. I sat in an uncomfortable plastic chair in my dorm’s lounge. "In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried," in particular, has quickly become one of a few seminal objects in my ways of thinking about the short story. It is a shepherd of an entire genre of hospital humor, and I mean this as much in tone, in attesting to the gravity of a situation, as I do in content.

Amy Hempel has an ear tuned to what it means to be dolefully aware of a situation’s consequence, yet equally aware of ones powerlessness in the face of that consequence. To the universal fear that there is more we can offer a person than our "presence." The narrator, in coming to terms with her best friend’s death, struggles with her perceived responsibility to offer whatever grand or sincere gesture seems required of a person in such a position.

Amy Hempel deals with this struggle brutally. The story hums with a certain background noise to the reality which neither woman ever acknowledges. The story, as drawn out of the two women's relationship, operates on a medium of humor, a shielding humor, the sort that comes when we find ourselves confusing humor with composure." — Jonah Vorspan-Stein, award winning fiction writer at UMass-Amherst

Amy Hempel has an ear tuned to what it means to be dolefully aware of a situation’s consequence, yet equally aware of ones powerlessness in the face of that consequence. To the universal fear that there is more we can offer a person than our "presence." The narrator, in coming to terms with her best friend’s death, struggles with her perceived responsibility to offer whatever grand or sincere gesture seems required of a person in such a position.

Amy Hempel deals with this struggle brutally. The story hums with a certain background noise to the reality which neither woman ever acknowledges. The story, as drawn out of the two women's relationship, operates on a medium of humor, a shielding humor, the sort that comes when we find ourselves confusing humor with composure." — Jonah Vorspan-Stein, award winning fiction writer at UMass-Amherst

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #3: Guest Post by Jamie Iredell

"I haven’t read a short story in a long time. I’m reading novels and book-length nonfiction. Lately, even in literary magazines, I’ve been turning to the nonfiction rather than the stories. I’ve been reading the things I’m reading because those are the things I’m writing, and I’m writing those things because it seems a natural progression to start off by writing short stories and “graduating” to writing novels. Also, as everyone knows, editors and agents want novels, not short story collections. I don’t think, though, that I’m not writing or reading short stories now because I want to give editors and agents what they “want.” I’m just doing what interests me now. It’s liberating to fall into a long work  (either reading or writing it), like a novel. In the book I’m working on I run off on tangents, explore characters that I’m pretty sure won’t be important to the overall book, get off on descriptions, record songs and dreams—all kinds of shit. I’m not really worried about what it is I’m producing. I suppose all that will eventually get honed in successive drafts. I don’t think I could work like that with a short story. Short stories thrive on focus, a minimized number of important characters, conflicts, and settings. But maybe I should explode all that in a short story. I never have before. I should try it and see what happens. A short story that does that is Rachel B. Glaser’s “Pee on Water.” It’s about everything. It’s amazing." — Jamie Iredell, author of The Book of Freaks

(either reading or writing it), like a novel. In the book I’m working on I run off on tangents, explore characters that I’m pretty sure won’t be important to the overall book, get off on descriptions, record songs and dreams—all kinds of shit. I’m not really worried about what it is I’m producing. I suppose all that will eventually get honed in successive drafts. I don’t think I could work like that with a short story. Short stories thrive on focus, a minimized number of important characters, conflicts, and settings. But maybe I should explode all that in a short story. I never have before. I should try it and see what happens. A short story that does that is Rachel B. Glaser’s “Pee on Water.” It’s about everything. It’s amazing." — Jamie Iredell, author of The Book of Freaks

(either reading or writing it), like a novel. In the book I’m working on I run off on tangents, explore characters that I’m pretty sure won’t be important to the overall book, get off on descriptions, record songs and dreams—all kinds of shit. I’m not really worried about what it is I’m producing. I suppose all that will eventually get honed in successive drafts. I don’t think I could work like that with a short story. Short stories thrive on focus, a minimized number of important characters, conflicts, and settings. But maybe I should explode all that in a short story. I never have before. I should try it and see what happens. A short story that does that is Rachel B. Glaser’s “Pee on Water.” It’s about everything. It’s amazing." — Jamie Iredell, author of The Book of Freaks

(either reading or writing it), like a novel. In the book I’m working on I run off on tangents, explore characters that I’m pretty sure won’t be important to the overall book, get off on descriptions, record songs and dreams—all kinds of shit. I’m not really worried about what it is I’m producing. I suppose all that will eventually get honed in successive drafts. I don’t think I could work like that with a short story. Short stories thrive on focus, a minimized number of important characters, conflicts, and settings. But maybe I should explode all that in a short story. I never have before. I should try it and see what happens. A short story that does that is Rachel B. Glaser’s “Pee on Water.” It’s about everything. It’s amazing." — Jamie Iredell, author of The Book of Freaks

Monday, May 2, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #2: Guest Post by Christy Crutchfield

"Short stories assigned in high school:

· Came from heavy textbooks with bodies of water on the cover.· Were often simple translations of fables and always had a definite moral.

· Provided good examples of metaphor.

· Provided characters that served the larger moral and did little else.

· Were unobtrusive and politely agreed with my Catholic school.

· Came with a lot of response questions.

I was not a reader.

Then, Ms. McPherson assigned “Parker’s Back.” At sixteen, I couldn’t articulate why I loved it, why I then chose to read the entire book, even the unassigned stories.

I’ll try now:

· The good guy wasn’t a good guy, and I was rooting for him.· Characters were spiteful, proud, wrong, and hungry.

· This hunger had nothing to do with a quest to kill a monster. I understood this hunger.

· Love was possibly not love and not easily won, even after a quest.

· There was metaphor, religious moral, but these were as complicated as the characters, complicated like my religion teachers were pretending Christianity wasn’t.

· It was difficult.

· At sixteen, my description of O’Connor’s language was: “Wow. Yes.”

This is still my description." — Christy Crutchfield, associate editor of Keyhole

Sunday, May 1, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #1: Guest Post by Ken Baumann

"A short story from another Mike–M Kitchell–possessed my computer. And Blake Butler's. We were laying out his story (Paul Garrior in Jacques Riverrun's "The Abyss Is The Foundation of the Possible") for the third issue of No Colony. This was the most difficult document we've ever built. I proffered myself at the altar of Word. I think I nearly killed a neighbor's dog, to appease this story. Blake had done most of the work, and then passed it to me, finished and ready to print, and then I opened it up and it garbled into some new fucked iteration. I had to manually address every space, every margin, flex and touch the images nicely. I thought about crushing my computer, I thought about headbutting the keyboard (I did do that, actually). Again, FINALLY, it was done, and then I opened it up to check it one more time and all the page numbers disappeared. I saw them go. There was a ghost in there. I don't know how I fixed it; I've heard many people go into fugue states under great duress. The story, though, Kitchell's short story, is one of my favorites and creates a zone of horror and confusion unlike anything I've read. But goddamn." — Ken Baumann, co-editor of No Colony and author of Solip

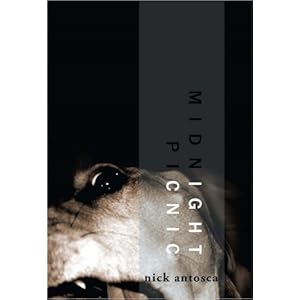

Getting In on the Action: NOÖ Knows Stories #0 (Featuring Nick Antosca)

We here at NOÖ are excited to play along with Short Story Month, championed by such stalwarts as the Emerging Writing Network and the Fiction Writers Review. Unlike those places, who are making very impressive and durable efforts to celebrate short stories, we at NOÖ are excited to unveil our weird and lazy plan, which is as follows:

I have emailed fifty cool people whose interesting thoughts on short stories I've A) heard or B) read, and I've invited those fifty people to "type 200 words as fast as they can" about a specific story. We will post these on this here NOÖ Journal blog, and here's hoping they will serve as supplements to the noble action happening elsewhere, like maybe they will be like Jell-O shots after the dinner.

Already we have our first participant, who just emailed me fifteen seconds ago, and who managed to impressively not follow the rules at all: Nick Antosca, author of Midnight Picnic—which is not a short story—and "Rachel Mia's Existence"—which is a short story—has written in to declare that: "A bad short story is like spinach but a good short story is like sex-flavored sorbet." Thanks for your efforts, Nick. Stay tuned for more!

Already we have our first participant, who just emailed me fifteen seconds ago, and who managed to impressively not follow the rules at all: Nick Antosca, author of Midnight Picnic—which is not a short story—and "Rachel Mia's Existence"—which is a short story—has written in to declare that: "A bad short story is like spinach but a good short story is like sex-flavored sorbet." Thanks for your efforts, Nick. Stay tuned for more!

I have emailed fifty cool people whose interesting thoughts on short stories I've A) heard or B) read, and I've invited those fifty people to "type 200 words as fast as they can" about a specific story. We will post these on this here NOÖ Journal blog, and here's hoping they will serve as supplements to the noble action happening elsewhere, like maybe they will be like Jell-O shots after the dinner.

Already we have our first participant, who just emailed me fifteen seconds ago, and who managed to impressively not follow the rules at all: Nick Antosca, author of Midnight Picnic—which is not a short story—and "Rachel Mia's Existence"—which is a short story—has written in to declare that: "A bad short story is like spinach but a good short story is like sex-flavored sorbet." Thanks for your efforts, Nick. Stay tuned for more!

Already we have our first participant, who just emailed me fifteen seconds ago, and who managed to impressively not follow the rules at all: Nick Antosca, author of Midnight Picnic—which is not a short story—and "Rachel Mia's Existence"—which is a short story—has written in to declare that: "A bad short story is like spinach but a good short story is like sex-flavored sorbet." Thanks for your efforts, Nick. Stay tuned for more!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)