Flannery O’Connor was everywhere. I read her in every town, in three states. It was “Good Country People” that got me. The smarmy Bible salesman and his side-part, he really thought he had everyone fooled, but I knew all about him.

Maybe the third time I’d read that story, freshman year in college, I had just broken with a fundamentalist religious group I’d belonged to for six years. Though I’d never met a Bible salesman, I recognized this character right away. I’d seen plenty of traveling preachers on tour, toting around their self-published books and Gospel CDs and charming Southern drawls. They visited our tiny congregations, young and inspired, often looking for a wife, preaching holiness, devotion, and reminding us that our daily focus should be the transcendence of our sinful flesh. As a teenager, I wanted to be one of them myself. I wanted to preach the word. I gave sermon-ettes on Sunday afternoons. I evangelized door-to-door. Then one day in Atlanta, I watched as one of those preachers committed a sin he had just, that day, preached against for an hour.

That moment opened up holiness for me, turned out its insides made of filthy rags. O’Connor’s Bible salesman opens up holiness, too—when he’s stolen Hulga’s wooden leg and finally unclasps his suitcase where all those Bibles are supposed to be.

Though I took a break from Flannery O’Connor after freshman year of college, I often re-told “Good Country People” in an effort to get friends to read her. I described that preacher in detail, and that moment when he opens the suitcase, and inside there are no Bibles, only glass eyeballs, wooden feet, wooden hands, hooks, and other prostheses pilfered from other girls in other barns. How his true calling is misusing religious devotion to cheat proud women out of their independence.

Last month, someone returned The Complete Short Stories to the library where I work. Thus ended my break from Flanner O’Connor. So many characters I delighted to watch yet again—serial killers, dishonest little boys, upstanding racists and oppressive mothers. I welcomed the South back into my heart and watched as O’Connor ripped it open, ripped the South open, slashing scissors through the great pillow of the South to find the iniquity hidden within. The struggle of goodness puffing itself up against evil until it deflates into a pathetic, mundane attempt of desperate people just trying to do OK.

I got to “Good Country People.” I was pleased—chatty neighbor, yes, she’s here, and here’s the judgmental mother, and the sour-puss atheist with the horse sweatshirt, and finally, the dopey potato-faced Bible salesman. This time, though, in the barn, when he opens his suitcase to throw in Hulga’s wooden leg, inside there are no prosthetic limbs or glass eyeballs or other stolen synthetic body parts. I had remembered the suitcase all wrong, and packed it, myself, with those limbs. Because really, in the story, his suitcase is empty, save for two Bibles. — Ella Longpre

Monday, June 27, 2011

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Little Monster Book

I had never heard of xTx or any of her writing when Mike gave me a copy of Normally Special and said, "You'll like this, it's really freaky." An introduction like that not only sparked my curiosity more than most conceivable things but made me compare xTx's writing t o what was perceived to be my taste in literature. The verdict is that Mike was right, I did like Normally Special, and my reaction was directly related to its high content of freaky (see also off-kilter, bizarre, uncomfortable, queer, and "wtf"). This book is the first of California-based writer who publishes under a pseudonym in part because she's written a lot of things she's described as too fucked up for people in her real life to read. Learning this was curiosity-sparker number two. Then I read the book, cried on pages 11-12, and from pretty much there on felt an extremely wide spectrum of emotions including humbled, warm, disconcerted, embarrassed, empowered, and hungry. xTx explores loneliness, violence, and sexuality when they appear in the most unlikely of situations. Her characters are multi-layered and are, for the most part, total freaking weirdoes. This collection of short stories tests the limits of what we can empathize with and is successful if at the very least for its ability to simultaneously shame and make champions out of its readers. More specifically, after I read this book, I realized what a freak I am. And that I kinda like it.

o what was perceived to be my taste in literature. The verdict is that Mike was right, I did like Normally Special, and my reaction was directly related to its high content of freaky (see also off-kilter, bizarre, uncomfortable, queer, and "wtf"). This book is the first of California-based writer who publishes under a pseudonym in part because she's written a lot of things she's described as too fucked up for people in her real life to read. Learning this was curiosity-sparker number two. Then I read the book, cried on pages 11-12, and from pretty much there on felt an extremely wide spectrum of emotions including humbled, warm, disconcerted, embarrassed, empowered, and hungry. xTx explores loneliness, violence, and sexuality when they appear in the most unlikely of situations. Her characters are multi-layered and are, for the most part, total freaking weirdoes. This collection of short stories tests the limits of what we can empathize with and is successful if at the very least for its ability to simultaneously shame and make champions out of its readers. More specifically, after I read this book, I realized what a freak I am. And that I kinda like it.

"An Unsteady Place" appears in the second half of the book and is about a woman vacationing with her husband and children at a beachside rental. The house they stay in is nautical-themed down to the handles of utensils. The idea of a fail-proof vacation with a perfect family is supposed to seem unsettling in this context, especially after the speaker says in what I imagine to be a pretty deadpan voice, "There is no way to make a mistake here." This is pretty much setting up everybody in the story for failure, and sure enough, a few pages later our protagonist can't look her children in the eyes because she's convinced they are turning into sea creatures that will devour her alive. She counts the starfish decals on the walls incessantly, and when she gets the same number everytime, the normalcy of that seems to drive her further into madness. "An Unsteady Place" is an example of a time where xTx creates a character who goes completely crazy for what seems to outsiders as irrational reasons, if they even notice the growing psychosis in the first place. Another example is in "The Mill Pond," which deals with a totally different kind of outcast, a chubby, pre-pubescent girl cursed with a bitterly ironic name - Tinkerbell. She toes the edge of what it means to feel sexual, and her underdeveloped sexuality, especially in relation to the polluted motives of the adult world around her, feels disturbing, if not ominous. Without making any kind of negative connotation about sex in general, this story, like "I Love My Dad. He Loves Me.", draws parallels not between sex and being sexy, but sex and estrangement from other humans. Something is really weird and sad about Tinkerbell laying on her back in the sun, pulling her shirt up to her "boobies," and rubbing her belly, alone with her thoughts. I thought for a second that I felt sorry for Tinkerbell and her contemporaries but this reaction was probably just a defensive one. You know how sometimes you pity or hate a quality in someone else because you actually just see it in yourself? I felt this way about Tinkerbell, which I think is a pretty cool/ intense reaction for a writer to get out of a reader. We surprise ourselves by never feeling better off or more sane than these characters, even when they are doing things like fantasizing about a boy named Fritos stabbing himself 33 times in the belly. Other than being compelling and often charmingly relevant, the characters xTx creates in these stories are remarkable for a reason I didn't fully understand until "I Am Not a Monster," the last story in the book. This story's title and most of its first page sound like a character statement of a suspiciously unreliable narrator. But then the narrator says this:

I think it's amazing how this character, despite functioning as a complete social outcast, is even a freak perceived by the rest of the freaks. The "freak elite" perhaps. Because she (I assume she is a "she," there is something astoundingly feminine about the majority of narrators in this book), has "too much to hold on to," she cannot fully embrace and be open with her nonconformity. She is certainly a monster, but in a way less tangible way than being green and slimy and living under your bed. That would make things too easy for her. Instead she must privately deviate from the average human emotions, desires, and fantasies. You can't pick her out of a crowd because she looks exactly like everyone else. Only she understands how fucked up she truly is, and this understanding brands her perpetually alone. "I Am Not a Monster" was a perfect end to Normally Special for me because I felt this really exciting catharsis where I was reminded of so many other characters in the book and how they are all secret freaks in the same strange, lonely, undisclosed way. I also started thinking about other secret freaks I know. I thought of Dexter and Dennis Cooper's George Miles. Monsters with pretty brown hair and healthy relationships with their dads. Chubby comic-book readers or young mothers at beachside vacation rentals. Anybody whose weirdness goes completely unsuspected by everyone else, and maybe even by themselves. xTx has said in interviews that she writes under a pseudonym to protect the people in her real life from seeing this ugly, dark, societally "wrong" side of her. It's like under the guise of this alternate persona, her inner freak is unleashed, free to be as wild and disgusting and honest as her characters wish they could be.

Anyways, if that's not incentive enough to read this book, then maybe I should mention its size. It's small enough to fit in my purse, which is so small that I can't carry around a normal wallet anymore. It's cute. It's a cute, unassuming, strange little read.

o what was perceived to be my taste in literature. The verdict is that Mike was right, I did like Normally Special, and my reaction was directly related to its high content of freaky (see also off-kilter, bizarre, uncomfortable, queer, and "wtf"). This book is the first of California-based writer who publishes under a pseudonym in part because she's written a lot of things she's described as too fucked up for people in her real life to read. Learning this was curiosity-sparker number two. Then I read the book, cried on pages 11-12, and from pretty much there on felt an extremely wide spectrum of emotions including humbled, warm, disconcerted, embarrassed, empowered, and hungry. xTx explores loneliness, violence, and sexuality when they appear in the most unlikely of situations. Her characters are multi-layered and are, for the most part, total freaking weirdoes. This collection of short stories tests the limits of what we can empathize with and is successful if at the very least for its ability to simultaneously shame and make champions out of its readers. More specifically, after I read this book, I realized what a freak I am. And that I kinda like it.

o what was perceived to be my taste in literature. The verdict is that Mike was right, I did like Normally Special, and my reaction was directly related to its high content of freaky (see also off-kilter, bizarre, uncomfortable, queer, and "wtf"). This book is the first of California-based writer who publishes under a pseudonym in part because she's written a lot of things she's described as too fucked up for people in her real life to read. Learning this was curiosity-sparker number two. Then I read the book, cried on pages 11-12, and from pretty much there on felt an extremely wide spectrum of emotions including humbled, warm, disconcerted, embarrassed, empowered, and hungry. xTx explores loneliness, violence, and sexuality when they appear in the most unlikely of situations. Her characters are multi-layered and are, for the most part, total freaking weirdoes. This collection of short stories tests the limits of what we can empathize with and is successful if at the very least for its ability to simultaneously shame and make champions out of its readers. More specifically, after I read this book, I realized what a freak I am. And that I kinda like it."An Unsteady Place" appears in the second half of the book and is about a woman vacationing with her husband and children at a beachside rental. The house they stay in is nautical-themed down to the handles of utensils. The idea of a fail-proof vacation with a perfect family is supposed to seem unsettling in this context, especially after the speaker says in what I imagine to be a pretty deadpan voice, "There is no way to make a mistake here." This is pretty much setting up everybody in the story for failure, and sure enough, a few pages later our protagonist can't look her children in the eyes because she's convinced they are turning into sea creatures that will devour her alive. She counts the starfish decals on the walls incessantly, and when she gets the same number everytime, the normalcy of that seems to drive her further into madness. "An Unsteady Place" is an example of a time where xTx creates a character who goes completely crazy for what seems to outsiders as irrational reasons, if they even notice the growing psychosis in the first place. Another example is in "The Mill Pond," which deals with a totally different kind of outcast, a chubby, pre-pubescent girl cursed with a bitterly ironic name - Tinkerbell. She toes the edge of what it means to feel sexual, and her underdeveloped sexuality, especially in relation to the polluted motives of the adult world around her, feels disturbing, if not ominous. Without making any kind of negative connotation about sex in general, this story, like "I Love My Dad. He Loves Me.", draws parallels not between sex and being sexy, but sex and estrangement from other humans. Something is really weird and sad about Tinkerbell laying on her back in the sun, pulling her shirt up to her "boobies," and rubbing her belly, alone with her thoughts. I thought for a second that I felt sorry for Tinkerbell and her contemporaries but this reaction was probably just a defensive one. You know how sometimes you pity or hate a quality in someone else because you actually just see it in yourself? I felt this way about Tinkerbell, which I think is a pretty cool/ intense reaction for a writer to get out of a reader. We surprise ourselves by never feeling better off or more sane than these characters, even when they are doing things like fantasizing about a boy named Fritos stabbing himself 33 times in the belly. Other than being compelling and often charmingly relevant, the characters xTx creates in these stories are remarkable for a reason I didn't fully understand until "I Am Not a Monster," the last story in the book. This story's title and most of its first page sound like a character statement of a suspiciously unreliable narrator. But then the narrator says this:

"I am the most timid of monsters. They have removed me from my position within their ranks citing words like fail, coward, reject, weakling, useless, stupid, worthless, dumbass. I tried to hang within their monster ranks, I did. I do. I try every day. It's a reenlisting of a reenlisting of a reenlisting. Every day I think, I am there and every day they kick me out. They make me go back to my life. They know what I know and that is, I have too much to hold on to so I cannot truly be a monster."

I think it's amazing how this character, despite functioning as a complete social outcast, is even a freak perceived by the rest of the freaks. The "freak elite" perhaps. Because she (I assume she is a "she," there is something astoundingly feminine about the majority of narrators in this book), has "too much to hold on to," she cannot fully embrace and be open with her nonconformity. She is certainly a monster, but in a way less tangible way than being green and slimy and living under your bed. That would make things too easy for her. Instead she must privately deviate from the average human emotions, desires, and fantasies. You can't pick her out of a crowd because she looks exactly like everyone else. Only she understands how fucked up she truly is, and this understanding brands her perpetually alone. "I Am Not a Monster" was a perfect end to Normally Special for me because I felt this really exciting catharsis where I was reminded of so many other characters in the book and how they are all secret freaks in the same strange, lonely, undisclosed way. I also started thinking about other secret freaks I know. I thought of Dexter and Dennis Cooper's George Miles. Monsters with pretty brown hair and healthy relationships with their dads. Chubby comic-book readers or young mothers at beachside vacation rentals. Anybody whose weirdness goes completely unsuspected by everyone else, and maybe even by themselves. xTx has said in interviews that she writes under a pseudonym to protect the people in her real life from seeing this ugly, dark, societally "wrong" side of her. It's like under the guise of this alternate persona, her inner freak is unleashed, free to be as wild and disgusting and honest as her characters wish they could be.

Anyways, if that's not incentive enough to read this book, then maybe I should mention its size. It's small enough to fit in my purse, which is so small that I can't carry around a normal wallet anymore. It's cute. It's a cute, unassuming, strange little read.

Thursday, June 2, 2011

Meet Phoebe Glick sounds like a teen rom com, but it's actually the title of this interview

That's right, Phoebe Glick is probably in some other disguise a rambunctious crime solver, but she's also the Summer 2011 NOÖ Journal/Magic Helicopter Press intern, and you'll be seeing her work around these here blog parts. Phoebe is a UMass Amherst student, a sub shop veteran, a fan of Biggie and Peaches, and a prolific blogger and photographer. When I first met her she told me "the weirder the better" when it came to literature, so I gave her a copy of God Jr. by Dennis Cooper and knew she'd fit into the NOÖ fold. To introduce her, here's a little Q&A:

Hi Phoebe! Where did you grow up? What is one interesting character you remember from your hometown?

I grew up in a small town in central Massachusetts called Holden. I tell people I'm from Worcester, which I hope sounds cooler, but which actually just sounds less clean. An interesting character I can think of on the top of my head is this guy who was always in the Holden Friendly's sitting with a cup of coffee and his briefcase open on the table at a ninety-degree angle. There were a bunch of wires and a computer screen in the briefcase. I went to Friendly's recently and he's totally sitting in the same booth, years after the last time I saw him. I'm pretty sure he's recording sounds.

What are some of your favorite books?

I love the Grapes of Wrath, Huckleberry Finn, and the Picture of Dorian Grey. In a broader sense, I like books with protagonists who are lonely or weird, and anything with a homoerotic subtext.

When did you first realize that language could make people feel things?

Probably when a woman from the Holden library read a ghost story to my second grade class about a creature that haunted a man for eating his tail. It made me feel a terror so real that I cried in the bathroom until my teacher sent someone in to ask me if I was having a "problem."

What is your favorite meal?

This is sort of complicated. Last summer I lived in Brooklyn for a month. Two feelings that will always characterize that time for me are that of being really hot and really poor. Perhaps to relieve these uncomfortable sensations, my food cravings took on the form of something light, heat-relieving, and expensive; more specifically: Pinkberry frozen yogurt. The first time I ate Pinkberry, my friend Lanny warned me that there was some kind of addictive ingredient in the pastel-colored, sweetly acidic, self-defined "swirly goodness." He also told me to order pomegranate flavor with raspberries and coconut shavings. It was love at first, uh, lick.

From reading your blog, I feel like you travel a lot. What are some of your strangest traveling experiences?

Once in Utah I almost drowned in a very strong whitewater rapid, and was brought to the shore by a six-foot-five-inch-tall blonde man whose spirit animal was a stallion and whose name was Tex. Because Tex spent so much time under the sweltering sun of the Western United States, cracks formed on the surfaces of his palms and he filled them with superglue to keep his skin together. Naturally, I fell in love with him. The way you fall in love with someone who saves your life. I'll never see him again.

Hi Phoebe! Where did you grow up? What is one interesting character you remember from your hometown?

I grew up in a small town in central Massachusetts called Holden. I tell people I'm from Worcester, which I hope sounds cooler, but which actually just sounds less clean. An interesting character I can think of on the top of my head is this guy who was always in the Holden Friendly's sitting with a cup of coffee and his briefcase open on the table at a ninety-degree angle. There were a bunch of wires and a computer screen in the briefcase. I went to Friendly's recently and he's totally sitting in the same booth, years after the last time I saw him. I'm pretty sure he's recording sounds.

What are some of your favorite books?

I love the Grapes of Wrath, Huckleberry Finn, and the Picture of Dorian Grey. In a broader sense, I like books with protagonists who are lonely or weird, and anything with a homoerotic subtext.

When did you first realize that language could make people feel things?

Probably when a woman from the Holden library read a ghost story to my second grade class about a creature that haunted a man for eating his tail. It made me feel a terror so real that I cried in the bathroom until my teacher sent someone in to ask me if I was having a "problem."

What is your favorite meal?

This is sort of complicated. Last summer I lived in Brooklyn for a month. Two feelings that will always characterize that time for me are that of being really hot and really poor. Perhaps to relieve these uncomfortable sensations, my food cravings took on the form of something light, heat-relieving, and expensive; more specifically: Pinkberry frozen yogurt. The first time I ate Pinkberry, my friend Lanny warned me that there was some kind of addictive ingredient in the pastel-colored, sweetly acidic, self-defined "swirly goodness." He also told me to order pomegranate flavor with raspberries and coconut shavings. It was love at first, uh, lick.

From reading your blog, I feel like you travel a lot. What are some of your strangest traveling experiences?

Once in Utah I almost drowned in a very strong whitewater rapid, and was brought to the shore by a six-foot-five-inch-tall blonde man whose spirit animal was a stallion and whose name was Tex. Because Tex spent so much time under the sweltering sun of the Western United States, cracks formed on the surfaces of his palms and he filled them with superglue to keep his skin together. Naturally, I fell in love with him. The way you fall in love with someone who saves your life. I'll never see him again.

Friday, May 27, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #12: Mark Cugini on Grace Paley

I've been riding Grace's dick for a while now. Grace dick-riders give her props for an assload of different reasons—her feminist activism, her colloquial voice, her clever insight, etcetera—but what she's so brilliantly adept at, I think, is owning the shit out of her shit.

This probably sounds vague. Good. It's supposed to. What I'm essentially saying is that when I read a Grace story, I know immediately that it's a Grace story, and this is what implores me to refer to her by her forename and her forename only because I'm sure you know exactly who I'm talking about.

Take "Wants," for example, which was the first Grace story I ever read. "Wants" is chock-full of all the necessary requirements we so frequently want from our fiction: conflict, that conflict's progression, an enormous change at the last minute. The thing, though, is that none of these elements are existing on their own but instead are eloquently unified for the sake of survival. It's sort of like what Gary Lutz said about words that are destined to belong together: without all of Grace's eloquences working towards one poignant whole, there would be no ripple effect, no rocking of the boat, and no Grace dick-riders.

And this, I argue, is what all fiction (or short stories or poems or novels or bathtubs) should be striving towards: an immense sense of ownership over the craft, a unity so strong that every last syllable is riding the current of one subtle ebb tide, easily drifting towards its own narrative coast so its readers can find it buried in sand. I'm supposed to be this romantic when I'm talking about these things, you see. If not, our stories will be lost forever, drifting further and further along on the endless current of boring, predictable prose. — Mark Cugini, editor of Big Lucks

This probably sounds vague. Good. It's supposed to. What I'm essentially saying is that when I read a Grace story, I know immediately that it's a Grace story, and this is what implores me to refer to her by her forename and her forename only because I'm sure you know exactly who I'm talking about.

Take "Wants," for example, which was the first Grace story I ever read. "Wants" is chock-full of all the necessary requirements we so frequently want from our fiction: conflict, that conflict's progression, an enormous change at the last minute. The thing, though, is that none of these elements are existing on their own but instead are eloquently unified for the sake of survival. It's sort of like what Gary Lutz said about words that are destined to belong together: without all of Grace's eloquences working towards one poignant whole, there would be no ripple effect, no rocking of the boat, and no Grace dick-riders.

And this, I argue, is what all fiction (or short stories or poems or novels or bathtubs) should be striving towards: an immense sense of ownership over the craft, a unity so strong that every last syllable is riding the current of one subtle ebb tide, easily drifting towards its own narrative coast so its readers can find it buried in sand. I'm supposed to be this romantic when I'm talking about these things, you see. If not, our stories will be lost forever, drifting further and further along on the endless current of boring, predictable prose. — Mark Cugini, editor of Big Lucks

Sunday, May 22, 2011

Todd Orchulek on The Lime Twig by John Hawkes

Ever wonder what would happen if those things you dream about but never, ever tell anyone about came true? Ever wonder what it would be like to live out your most depraved fantasies, you know, the ones that only come creeping out of your subconscious under the cover of darkness, behind the shadow of dream? Well, John Hawkes certainly has, and he was kind enough to share. The Lime Twig is the thing, and it’s a fever I have never quite gotten over. I first read it the summer before transferring to UMass and it’s one of the things that Mike and I talked about at our first meeting, where I landed my internship, NOÖ style. It was fitting that I had read it in the haze of summer, in a field, under the watchful eye of shape shifting clouds. The free association feel felt right. I named clouds. I listened to the brittle music of Hawkes's narrative, snapping the lives of the bored Banks and the unfortunate Hencher in two. I watched them squirm under the long scrutiny of Hawkes's wish-fulfillment-gone-awry microscopic lens.

It all happens in the name of love, somehow, for as Hawkes says, “Love is a long scrutiny like that.” If you know nothing else about Hawkes’s style, you should know that. The quote is applicable to the whole. The narrative lens filters like consciousness itself. It’s discriminatory, distracted and spastic. But there’s always love and there’s always terror; the two are forever inextricably intertwined, just like in life. And that’s what it’s all about, really. It’s like a study in love and terror and desire and the places where those things meet, and it’s all wrapped up in a tasty poetic prose tortilla. There’s also a horse and kidneys cooling on the ledge. Hawkes's other works - The Blood Oranges, or Death, Sleep and the Traveler explore similar areas, but in different ways, mostly without the overt sense of terror, and without the sinking feeling that The Lime Twig can give you. The Cannibal might be a sister to The Lime Twig, and, really, you can’t go wrong reading any of his stuff if you’re even a tiny bit curious. Finding Hawkes was, for me, like stumbling across some fantastic secret or discovering some previously unknown, underground band that you feel right away, from the first beat, the first note. I remember, straight off, I wanted to simultaneously share and not share it, him, with the rest of the world. I wanted to keep him all to myself, but in the end I knew I couldn’t do that. He’s too good. So here I am, shouting from the rooftops.

It’s that long sense of scrutiny that holds it all together, all the out of focus elements, the fuzzy in-betweens, the moments of reflection. Hawkes' ability to hone in on the most minute details renders certain scenes lucid, even transcendent. You’ll feel like you’re dreaming, or reading a dream, if that’s even possible. Some say it isn’t, but I disagree. I’ve done homework in dreams before. Yes, that’s about as exciting as it sounds, and no, that wouldn’t be an example of the kind of dream Hawkes' is talking about here. So don’t worry, or do, if you’re afraid of the dark, because this book is full of shadows. Read it in a well lit room. The narrative thrust oftentimes leads you into moments of uncomfortable clarity precisely because of its capacity to convey a sense of terror with a single image. Or just clarity, depending. You’ll find yourself immersed in an image, a smell, a sound—the smell of lime, the image of the horse, a pair of buttocks, or the sound of footsteps a floor below. You’ll wonder how you ended up there, but not how the narrative ended up there. And that’s an important distinction, because wherever the story goes, it feels right, even when things go wrong. It feels hyper real. You don’t wonder about it, while you’re reading, because it’s so brilliantly rendered. It’s only after you’re done (which won’t be long – at 175 pages, it is more novella than novel) that you stop and think, wait, what?

And the imagery haunts. Measured against those moments of intense, long scrutiny, the rest of the time things simply aren’t as clear, as is often the case with life, or dreams. That’s where it becomes, for me, “magic time” as Kevin Spacey would say (doing his best Jack Lemon impersonation), because it is a dream, after all. And like a dream, this novel is filled with those moments of transition, where identity and focus become blurred and fuzzy—people go in and out of focus, images appear and disappear, time speeds up or slows down without you even noticing. And then, boom goes the dynamite, things suddenly snap back into focus. And it’s a clear, lucid, sick focus that Hawkes throws at us. It’s a sharp, frayed, lyrical focus.

As for the story, well, Hencher’s the way in. He’s a fat man, missing his mother, living in the past. He finds a new outlet for his loyalty, the misoneist Banks, Michael and Margaret. Hencher wants to please them, to show what a loyal dog he really is, so he decides to help Michael fulfill his dream, owning a race horse. It’s a dream that everyone seems privy to, Michael and Margaret and Hencher, too. It affects all of them, the dream and the horse. Their lives and relationships are inextricably tied to that horse, Michael’s dreams, and their own.

“You may manipulate the screen now, William,” Hencher’s mother tells him in flashback, and he does. Hawkes does, too, subtly shifting perception and summoning tension at will, with a deft turn of phrase, or an image, suspended. He messes with holotropics, hanging the image of the horse in the middle of the narrative, in the Banks’ apartment, teasing and toying with the reader and reality. It’s unnerving, but an effective narrative mechanism:

“Knowing how much she feared his dreams; knowing that her own worst dream was one day to find him gone, overdue minute by minute some late afternoon until the inexplicable absence of him became a certainty; knowing that his own worst dream, and best, was of a horse which was itself the flesh of all violent dreams; knowing this dream, that the horse was in their sitting room-he had left the flat door open as if he meant to return in a moment or meant never to return-seeing the room empty except for moonlight bright as day and, in the middle of the floor, the tall upright shape of the horse draped from head to tail in an enormous sheet that falls over the eyes and hangs down stiffly from the silver jaw; knowing the horse on sight and listening while it raises one shadowed hoof on the end of a silver thread of foreleg and drives down the hoof to splinter in a single crash one plank of that empty Dreary Station floor; knowing his own impurity and Hencher’s guile; and knowing that Margaret’s hand has nothing in the palm but a short life span (finding one of her hairpins in his pocket that Wednesday dawn when he walked out into the sunlight with nothing cupped in the lip of his knowledge except thoughts of the night and pleasure he was about to find)-knowing all this, he heard in Hencher’s first question the sound of a dirty wind, a secret thought, the sudden crashing in of the plank and the crashing shut of that door.”Once Michael gets involved with Hencher and his mob friends, things begin to change for everyone, and not for the better. Michael is spared, for a spell, and gets to live out his most lurid fantasies. Margaret and Hencher, well, not so much. It all quickly devolves into a nightmare from there. The chrysalis doesn’t change into a butterfly, but a beast.

What Hawkes does best is manipulate time. In this study of reality vs. unreality, or fantasy vs. nightmare, this has the greatest effect on the narrative. He has it on a string throughout, speeding it up, slowing it down, or suspending it altogether. He flashes forward, flashes back. He does away with it completely when it becomes burdensome. This allows the terror to bloom fully within the reader’s mind. And the image of the horse resonates and echoes throughout, from start to finish, for temporality has no dominion in the realm of dream or nightmare. For

Michael, and for me, it carries with it an eerie, undeniable sense of jamais vu.

Michael, and for me, it carries with it an eerie, undeniable sense of jamais vu.So, be careful what you wish for, or, at least, remember what that old adage, “if you can’t be good, be careful,” because who knows, there might be a horse out there somewhere with your name on it.

Thursday, May 19, 2011

NOÖ Knows Stories #11: Carolyn Zaikowski on The Little Prince

|

| Carolyn Zaikowski's tattoo: "I believe that for his escape he took advantage of the migration of a flock of wild birds." |

I do not say these things lightly nor to invoke cliché. The Little Prince is not just a "cute" book to me, my love of it not just a quirky or fun part of my identity. Each year I wonder, is this the right year to give it to my nephew, himself a little prince? At what age will he finally understand, and what does understanding mean? Perhaps it's I, in my self-satisfied adulthood, who has fallen from wonder and needs to be reminded that a plain hat and an elephant being eaten by a snake are not the same thing? I keep it next to my bed in a small pile of crucial books that includes Gandhi's autobiography, S.N. Goenka's guide to Vipassana Meditation, the Bhagavad Gita, and an archive of Thich Nhat Hanh. When a friend of mine died, it was The Little Prince we read at her funeral: "And at night you will look up at the stars. Where I live everything is so small that I cannot show you where my star is to be found. It is better like that. My star will just be one of the stars, for you. And so you will love to watch all the stars in the heavens... they will all be your friends. In one of the stars I shall be living. In one of them I shall be laughing. And so it will be as if all the stars were laughing, when you look at the sky at night. And when your sorrow is comforted (time soothes all sorrows) you will be content that you have known me." In my dark moments, I think of this. I go out to the hill behind my house, alone, and I am reminded of the expanse—sad here, glorious there, but every inch of which proves the impossibility of aloneness. When Antoine de St. Exupery's plane, which crashed and killed him in 1944, was found in 2004, a rush of heat filled my esophagus and pulse and I felt humbled with wonder. It is so good to remember wonder. "Is the warfare between the sheep and flowers not important? Is this not of more consequence than a fat red-faced gentleman's sums?" There is a small group of indigenous people in Argentina who speak Toba, a language into which only two books have been translated in modern memory: The Bible and The Little Prince. There is a reason why. — Carolyn Zaikowski, editor of Dinosaur Bees

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

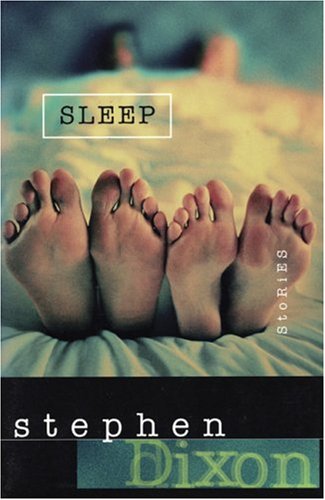

NOÖ Knows Stories #10: Bradley Sands on Stephen Dixon's "The Stranded Man"

|

| Stephen Dixon |

I always found it more difficult to get into Dixon’s story collections than his novels. At first, I am unable to read more than one story per day. Eventually, I really get into the books and try to read them in their entirety in a day because it feels like I have acquired the ability to enjoy more than one story in one sitting and if I don’t take advantage of this ability, I will lose it and go back to only being able to read one story per day. Since I don’t like reading story collections that way, I try to devour the entire book in one sitting if possible.

I checked his collection, Sleep, out from the library about 8 months ago. I was only able to get through a couple of stories before returning it because I had banned myself from reading adult fiction books to prepare for the endeavor of writing a novel for children. After finishing the novel, I checked the book out from the library again. I read a few stories here and there and it took me a while to gain the ability to enjoy more than one story per day. But I achieved the ability today and finished the book.

Regarding Dixon’s writing, he often uses protagonists who obsess over every decision and detail of their past, present, and futures. Obsessing about the future stands out in particular because the characters often consider the many ways in which events can occur in their lives and the stories include their rapidly changing speculations. I see this as a commentary on how every person on this planet is a storyteller because we all speculate about our futures, although perhaps not to the same extent as Dixon’s protagonists. This sort of speculation is very prominent in Sleep, or at least in the first fourth of the book or so.

I’m going to comment about a story that I read about a week or two ago: “The Stranded Man.” In the beginning, the protagonist starts out by describing his life on a deserted island and how he is lying in a hammock. Within a few sentences, he says, “Not quite a hammock. Nothing like one. On some dried grass, in a hut.” Upon reading this, it becomes a typical Dixon story. If this were a person’s introduction to his work, their sense of the story’s reality will be disrupted. For those who are already familiar with Dixon’s writing, these sentences reveal that the protagonist is imagining that he is on a deserted island. For about a page and a half, the protagonist continues to describe his life on the island and keeps changing his mind about certain details. Then it is revealed that he is not on a deserted island. Instead, he is at home, lying next to his wife in bed. He tells her that he was thinking about how he would be able to get himself to a deserted island that was thousands of miles from all bodies of land and be able to survive for years without being found. The idea of being alone is very appealing to him. The man’s wife does not seem bothered by this, but this is not a surprise in a Dixon story. The man tries to figure out how he would end up alone on a deserted island in a way that would not result in anyone’s death, but he cannot conceive of a scenario that would be successful. The wife suggests swimming to the island, but he says it would be too far. Neither he nor she come up with the idea that he could go alone to the island in a boat, although I suppose that wouldn’t work so well considering he would have a means to leave the island, but he could always destroy the boat. Soon, the man speaks of the “stranded man” of his fantasy as if he were a separate person from himself. His wife falls asleep and he continues to contemplate ways to reach the island. He imagines meeting a native girl and becoming her lover. They have children together. No, he never meets a native girl. He fantasizes that his wife is a native girl. After years, he is rescued. His island family comes back with him to the United States. No, they does not. His wife remarried while he was missing. He grows old and dies in the native girl’s arms. No, they go back to the island. Their children decide to stay behind and have children of their own. The man’s children sometimes visit their parents. He dies on the island. Or does he? — Bradley Sands, author of Rico Slade Will Fucking Kill You and editor of Bust Down the Door and Eat All the Chickens

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)